How to Fact Check Your Favourite Wellness and Health Blog and avoid Fake Health News

In the December 2014 issue of ELLE Australia, Elle published a feature titled 'The Most Inspiring Woman You've Met This Year' after she blogged about beating terminal brain cancer through alternative therapies. Thousands of followers bought her tale of healing through clean eating.

Questions about Gibson began to arise in 2015, when she failed to donate the $320,000 she’d promised from sales of her app and cookbook, through her company The Whole Pantry. From there, the truth started spilling out.

Gibson never had cancer. She lied about her life, her background, and even her age. Everything The Whole Pantry was based on had been fabricated.

Last week, the shocking story came to a conclusion when an Australian federal court in Melbourne ordered Gibson to pay $320,000 back to the state of Victoria for lying about charitable donations.

The internet can be a great resource, depending on how you use it. And amongst the false claims, there’s good information. It’s the ability to find that information that should be taught and shared.

Any time you read about a new trend or health claim, you should ask yourself these questions before jumping to any conclusions:

1. Are there any scientific studies that back up this claim, and are they recent?

If yes, the studies should be about human participants (the larger sample size, the better) and not animals. Animals are often placed in unrealistic situations — for example, exposed to toxins at levels humans would rarely naturally be exposed to.

How recent the studies are matters, too. Unless the claims are conclusively proven (meaning no further research is needed), a study from the 1980s shouldn’t pass your smell test.

2. Does the claim really equal a ‘cure’ or is it just a preventative or protective effect?

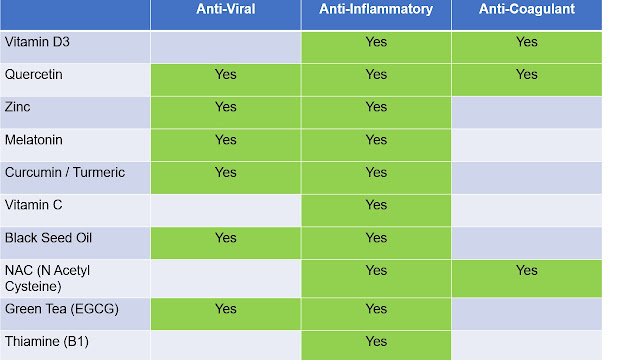

A lot of products claim to be treatments and cures, using buzzwords with the prefix “anti,” such as antioxidant, anticancer, anti-aging, and more. Many brands will cling to these terms and flip the definition so a product becomes synonymous with “treatment,” giving the impression that it’s a “cure.”

However, many studies report protective and preventative effects rather than cures. Alternative remedies may provide some relief or improvement, but they’re unlikely to reverse a condition or ailment.

3. Is the story sponsored, selling something, or just simply has ads?

In the age of the internet, everything costs something. If you’re not spending dollars, then you’re spending your attention. With that attention, you’re spending time building familiarity and trust with a certain brand. This is why you see unrelated and related ads sometimes, because businesses pay for the space. That payment is how content, and the teams behind them, live.

In cases where stories aren’t sponsored by another brand, try to look at the extent of which something is being sold. At the end of the post, you can always ask, “Were they selling me information I can use or a product to use?” When it comes to health — especially chronic conditions — choose a site that prioritizes information first. Information is something you can take to a professional for a second opinion. Products and their variations will wait for you.

4. Is the expert a real, verified expert?

Anyone can claim they went to Harvard, but it doesn’t mean they graduated. It’s important to check whether an expert is practicing or well-respected within the field. Likewise, you shouldn’t disregard information only because it doesn’t come from a doctor. Instead, look at a website’s sources and editorial process.

|

| This is a sample fake health news! |

Questions about Gibson began to arise in 2015, when she failed to donate the $320,000 she’d promised from sales of her app and cookbook, through her company The Whole Pantry. From there, the truth started spilling out.

Gibson never had cancer. She lied about her life, her background, and even her age. Everything The Whole Pantry was based on had been fabricated.

Last week, the shocking story came to a conclusion when an Australian federal court in Melbourne ordered Gibson to pay $320,000 back to the state of Victoria for lying about charitable donations.

The internet can be a great resource, depending on how you use it. And amongst the false claims, there’s good information. It’s the ability to find that information that should be taught and shared.

Any time you read about a new trend or health claim, you should ask yourself these questions before jumping to any conclusions:

1. Are there any scientific studies that back up this claim, and are they recent?

If yes, the studies should be about human participants (the larger sample size, the better) and not animals. Animals are often placed in unrealistic situations — for example, exposed to toxins at levels humans would rarely naturally be exposed to.

How recent the studies are matters, too. Unless the claims are conclusively proven (meaning no further research is needed), a study from the 1980s shouldn’t pass your smell test.

2. Does the claim really equal a ‘cure’ or is it just a preventative or protective effect?

A lot of products claim to be treatments and cures, using buzzwords with the prefix “anti,” such as antioxidant, anticancer, anti-aging, and more. Many brands will cling to these terms and flip the definition so a product becomes synonymous with “treatment,” giving the impression that it’s a “cure.”

However, many studies report protective and preventative effects rather than cures. Alternative remedies may provide some relief or improvement, but they’re unlikely to reverse a condition or ailment.

3. Is the story sponsored, selling something, or just simply has ads?

In the age of the internet, everything costs something. If you’re not spending dollars, then you’re spending your attention. With that attention, you’re spending time building familiarity and trust with a certain brand. This is why you see unrelated and related ads sometimes, because businesses pay for the space. That payment is how content, and the teams behind them, live.

In cases where stories aren’t sponsored by another brand, try to look at the extent of which something is being sold. At the end of the post, you can always ask, “Were they selling me information I can use or a product to use?” When it comes to health — especially chronic conditions — choose a site that prioritizes information first. Information is something you can take to a professional for a second opinion. Products and their variations will wait for you.

4. Is the expert a real, verified expert?

Anyone can claim they went to Harvard, but it doesn’t mean they graduated. It’s important to check whether an expert is practicing or well-respected within the field. Likewise, you shouldn’t disregard information only because it doesn’t come from a doctor. Instead, look at a website’s sources and editorial process.

This isn’t the first unsubstantiated health claim on the internet

In April, Michelle Phan, one of the original beauty vloggers on YouTube, went viral for opening up about depression. But in an interview with Racked, she’s quoted saying she’s never received a diagnosis from a medical professional. Instead, she got her diagnosis from quizzes on the internet. This isn’t to say her feelings weren’t valid, but her admission of treatment she used for herself (travel) is irresponsible to people in her audience who may require a diagnosis and professional help.

But Gibson isn’t the only influencer capitalizing on the wellness movement through her brand.

In July, television host John Oliver reported on Alex Jones of InfoWars, who pushes vitamins and “nutriceuticals” on his news show. Jones reportedly uses a “doctor” with no medical background to back up his supplements.

In August, The Outline published an exposé on David “Avocado” Wolfe, who has 11 million followers on Facebook and claims his red-wine-infused chocolate bars can make you live longer (there’s no evidence of this).

Vice often exposes YouTubers, other wellness trends, and influencers for making inaccurate health claims that can potentially cause harm.

More recently, the nonprofit Truth in Advertising sued Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness blog, for “expressly or implicitly, [claiming] that its products — or third-party products that it promotes — can treat, cure, prevent, alleviate the symptoms of, or reduce the risk of developing a number of ailments, ranging from depression, anxiety, and insomnia, to infertility, uterine prolapse, and arthritis, just to name a few.”

Somewhere along the way, our thirst for information has only landed us on a stockpile of misinformation. That’s part of what makes The Whole Pantry fiasco so frightening.

In an ideal world, I wish we could read information and take it in “good faith” as publisher Penguin Books Australia did, according to The Guardian, when they published Belle Gibson’s cookbook. Being skeptical is stressful, and it’s hard work. But when it comes to health, it’s work that pays off.

Science hasn’t come to conclusions on many treatments, many of which haven’t even been studied yet. So that’s why I leave you with this checklist. I hope it empowers you to take control of your health journey, instead of leaving it in anonymous hands.

In April, Michelle Phan, one of the original beauty vloggers on YouTube, went viral for opening up about depression. But in an interview with Racked, she’s quoted saying she’s never received a diagnosis from a medical professional. Instead, she got her diagnosis from quizzes on the internet. This isn’t to say her feelings weren’t valid, but her admission of treatment she used for herself (travel) is irresponsible to people in her audience who may require a diagnosis and professional help.

But Gibson isn’t the only influencer capitalizing on the wellness movement through her brand.

In July, television host John Oliver reported on Alex Jones of InfoWars, who pushes vitamins and “nutriceuticals” on his news show. Jones reportedly uses a “doctor” with no medical background to back up his supplements.

In August, The Outline published an exposé on David “Avocado” Wolfe, who has 11 million followers on Facebook and claims his red-wine-infused chocolate bars can make you live longer (there’s no evidence of this).

Vice often exposes YouTubers, other wellness trends, and influencers for making inaccurate health claims that can potentially cause harm.

More recently, the nonprofit Truth in Advertising sued Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness blog, for “expressly or implicitly, [claiming] that its products — or third-party products that it promotes — can treat, cure, prevent, alleviate the symptoms of, or reduce the risk of developing a number of ailments, ranging from depression, anxiety, and insomnia, to infertility, uterine prolapse, and arthritis, just to name a few.”

Somewhere along the way, our thirst for information has only landed us on a stockpile of misinformation. That’s part of what makes The Whole Pantry fiasco so frightening.

In an ideal world, I wish we could read information and take it in “good faith” as publisher Penguin Books Australia did, according to The Guardian, when they published Belle Gibson’s cookbook. Being skeptical is stressful, and it’s hard work. But when it comes to health, it’s work that pays off.

Science hasn’t come to conclusions on many treatments, many of which haven’t even been studied yet. So that’s why I leave you with this checklist. I hope it empowers you to take control of your health journey, instead of leaving it in anonymous hands.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

Comments