Determinants of Human Longevity: Evidence-Based Lifestyle and Metabolic Interventions (2026)

Abstract

Longevity is influenced by a combination of genetic, behavioral, and environmental factors. This review synthesizes evidence on modifiable determinants of lifespan, emphasizing metabolic health, physical fitness, sleep, psychosocial factors, and behavioral interventions. Epidemiologic and interventional studies indicate that preserving muscle mass, maintaining cardiorespiratory fitness, optimizing metabolic markers, and sustaining social connectedness confer substantial reductions in all-cause mortality. Practical strategies, including resistance training, moderate-intensity aerobic activity, caloric moderation, sleep hygiene, and stress management, are highlighted as high-impact, evidence-supported interventions to extend healthspan.

Keywords: longevity, insulin resistance, metabolic health, muscle mass, cardiorespiratory fitness, sleep, stress management, healthspan

1. Introduction

Human longevity is determined by complex interactions between genetics and lifestyle. While genetic factors account for approximately 20–30% of lifespan variation, modifiable behaviors account for the majority of early mortality risk (Fontana et al., 2010). Chronic metabolic dysfunction, sedentary behavior, poor sleep, and psychosocial stress have emerged as key contributors to premature mortality.

Conceptual Framework: Think of lifespan as a stack. If the bottom layers are weak, nothing on top matters. This framework highlights that interventions targeting foundational aspects such as metabolic health, muscle mass, and cardiovascular fitness are prerequisites for effective longevity strategies.

This review evaluates the evidence for interventions that preserve metabolic function, physical performance, and psychosocial health to support healthy aging.2. Metabolic Health and Longevity

2.1 Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinemia

Insulin resistance is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality (Taylor et al., 2013). Caloric restriction and dietary modification improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility. In the CALERIE Phase 1 study, a 6-month calorie restriction intervention in overweight adults reduced fasting insulin and induced metabolic adaptation, demonstrating effects on biomarkers associated with aging (Heilbronn et al., 2006). Long-term interventions, as seen in CALERIE Phase 2 (2-year RCT), further confirm sustained weight loss, decreased metabolic rate adjusted for weight change, and reductions in triiodothyronine (T3) and inflammatory markers, indicating potential impacts on healthspan (Most et al., 2015).

2.2 Body Composition

Preservation of lean mass is critical. Sarcopenia independently predicts frailty, morbidity, and mortality (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2010). Resistance training at least 2–3 times per week preserves muscle strength and function, mitigating age-related metabolic decline.

3. Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is a robust predictor of mortality. Higher VO₂max levels are inversely associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Kodama et al., 2009). Evidence indicates that moderate-intensity aerobic activity (150 min/week) combined with high-intensity interval training 1–2 times per week optimizes metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes.

Here’s a polished and reviewed version of the University of Sydney news article you shared, rewritten for clarity, SEO value, and journalistic flow while keeping all key factual details:

Improving Sleep, Diet & Physical Activity Could Help People Live Longer — Sydney Uni Study (2026)

Two large studies suggest that taking small steps—such as moving a little more, going to bed slightly earlier, or eating a few more vegetables—can significantly improve your quality of life and reduce the risk of early death, especially among people starting from the least healthy habits.The research, published in The Lancet and eClinicalMedicine, and involving nearly 200,000 participants, offers encouraging news for anyone who finds dramatic lifestyle overhauls overwhelming. For most people, doing just a little more may be enough to move the needle.

Small, achievable changes to daily habits — like sleeping a few extra minutes, eating slightly better, and moving more — may substantially increase both lifespan (years lived) and healthspan (years lived free of major disease), according to new research led by the University of Sydney. (sydney.edu.au)

Study HighlightsResearchers from the Mackenzie Wearables Hub and Charles Perkins Centre explored how daily sleep, diet quality, and physical activity interact to influence long-term health. Their findings, published in eClinicalMedicine (2026), suggest that even modest lifestyle improvements can produce measurable gains. (sydney.edu.au)

For individuals with the poorest habits in all three areas, adding just:

5 extra minutes of sleep

~2 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (e.g., brisk walking, stairs)

An additional half-serving of vegetables per day

…was associated with an estimated 1 additional year of life over people with the least healthy patterns. (sydney.edu.au)

When behaviors were closer to optimal standards — around 7–8 hours of sleep, 40+ minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per day, and a healthy diet — participants were linked with more than 9 additional years of lifespan and healthy years compared to those with the worst habits. (sydney.edu.au)

Lead researcher Dr Nicholas Koemel explained that while sleep, diet, and exercise are individually linked to better health, studying them together shows their combined positive impact over time. (sydney.edu.au)

Supporting Evidence from a Second StudyA companion paper co-led by Professor Melody Ding from Sydney’s School of Public Health looked at physical activity alone using data from more than 135,000 adults across multiple cohorts. Key insights included: (sydney.edu.au)

Walking just 5 extra minutes at a moderate pace per day was connected with a ~10% lower chance of early death for most adults. (sydney.edu.au)

People who spent about 10 hours per day sedentary and reduced that by 30 minutes saw an estimated ~7% reduction in all-cause mortality. (sydney.edu.au)

Professor Ding emphasized that even small increases in physical activity can have major public-health benefits, especially for people who are currently very inactive. (sydney.edu.au)

Why This Matters

These studies reinforce a growing body of evidence that small lifestyle improvements — especially when combined — are more achievable and powerful than extreme changes in one behavior alone. Research using large tracking datasets like the UK Biobank supports this synergistic effect between sleep, diet, and movement. (EurekAlert!)

4. Sleep and Circadian Health

Sleep duration and quality are strongly linked to longevity. Adults obtaining 7–8 hours of quality sleep per night demonstrate lower rates of cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and mortality (Cappuccio et al., 2010). Regular sleep-wake cycles, nocturnal darkness, and temperature regulation support endocrine and metabolic homeostasis.

Sleep emerged as one of the strongest predictors of how long you live — When researchers compared major lifestyle risks, sleep deprivation consistently ranked among the strongest predictors of early death. It rivaled obesity and surpassed physical inactivity and socioeconomic factors, placing sleep alongside smoking as a dominant influence on lifespan. The data suggest that insufficient sleep acts as a primary driver of mortality, independent of other healthy habits like exercise and diet.

The study tracked young adults who recorded their meals and wore sleep monitors. Those who ate more fruits, vegetables, and healthy carbs like whole grains experienced deeper, more restful sleep with fewer wakeups during the night.

Experts say even one day of healthy eating can make a difference. Adding more fruits and vegetables to your meals may be a simple, natural way to improve your sleep.

ii. The Effects of Exercise and Sleep on Brain Health - 2023 Study

Those who had higher levels of physical activity and slept an optimal number of hours had the slowest cognitive decline. Overall, the data suggested that higher-intensity physical activity was not enough to mitigate the rapid cognitive decline that is associated with insufficient sleep.

5. Stress and Psychosocial Factors

Chronic stress accelerates biological aging via elevated cortisol, inflammation, and immune dysregulation (Epel et al., 2004). Social isolation independently increases mortality risk comparable to smoking (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Interventions such as mindfulness, moderate exercise, and nature exposure mitigate stress-related mortality risk.

At the summit, he spoke about his vision of how to get America healthy, promoting a radical Scandinavian-style approach to health that would include raising the minimum wage, providing more affordable housing and improving educational outcomes.

“Modern medicine actually has relatively little role to play in terms of your health,” he says, arguing that “maybe 10 per cent of life expectancy or health is determined by what your doctor prescribes for you in the hospital or in the clinic”.

Instead, he says socially determined factors – the “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age” – are the greatest contributors to overall health.

“If you are somebody who is in a low-pay, low-control, high-demand job, that, in a way, is effectively a death sentence in terms of the chronic stress it exerts,” he says.

6. Evidence-Based Lifestyle Recommendations

Metabolic Health: Caloric moderation, insulin-sensitizing dietary patterns

Muscle Mass: Resistance training ≥2×/week, adequate protein intake

Cardiorespiratory Fitness: 150 min/week moderate aerobic + 1–2 HIIT sessions

Sleep: 7–8 h/night, consistent sleep-wake schedule

Stress Management: Mindfulness, social engagement, nature exposure

Behavioral Compliance: Sustained adherence to lifestyle interventions

7. The Longevity Hierarchy (What Actually Moves the Needle)

The “don’t die early” framework that actually works in the real world — not biohacker cosplay. Think of lifespan as a stack. If the bottom layers are weak, nothing on top matters.

1️⃣ Don’t Die from Preventable Causes

This alone removes a massive chunk of early mortality risk.

Non‑negotiables

Seatbelt, helmet, sober driving

Don’t smoke (nothing offsets this)

Alcohol ≤ light / occasional

Don’t ignore chest pain, neuro symptoms, unexplained weight loss.

2️⃣ Muscle = Survival Tissue

After ~40, muscle mass predicts:

All‑cause mortality

Cancer outcomes

Falls, fractures, disability

Minimum effective dose

Resistance training 2–3×/week

Focus: legs, hips, back, grip

Goal: not aesthetics — functional strength at 80+

📌 If you only do one thing: lift weights and keep lifting forever.

3️⃣ Cardiorespiratory Fitness (VO₂max)

VO₂max is one of the strongest predictors of lifespan ever measured.

Targets

Zone 2 cardio: 3–5 hrs/week (brisk walking, cycling)

1–2 short high‑intensity sessions/week

Even modest fitness beats most drugs.

4️⃣ Metabolic Health (The Silent Killer)

Key markers to protect

Waist circumference

Fasting glucose & insulin

Triglyceride/HDL ratio

Blood pressure

Principles

Avoid chronic hyperinsulinemia

Preserve metabolic flexibility

Eat protein first, fiber second, carbs last (most days)

5️⃣ Sleep Is a Longevity Multiplier

Short sleep increases:

Cancer risk

Cardiovascular mortality

Dementia risk

Rules

Same sleep/wake time

Dark, cool room

Morning light exposure

No heroics here — just protect it

6️⃣ Stress & Nervous System Regulation

Chronic stress accelerates aging via:

Cortisol

Inflammation

Immune suppression

You don’t need meditation retreats.

You need downshifts:

Walking

Breathing

Nature

Low‑stakes joy

7️⃣ Relationships

Strong social ties:

Reduce mortality risk by ~30–50%

Improve recovery from illness

Protect mental health

One or two deep connections beat a thousand followers.

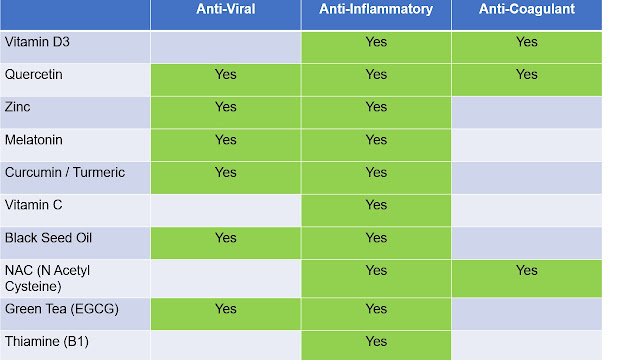

8️⃣ Supplements & “Longevity Drugs” (Last Layer)

Only after the above.

Evidence‑leaning basics

Vitamin D (if deficient)

Omega‑3s (food > pills)

Magnesium (sleep/stress)

Everything else = marginal until foundations are solid.

The Anti‑Longevity Traps to Avoid

❌ Obsessing over biomarkers while neglecting fitness

❌ Extreme restriction → muscle loss

❌ Chronic stress masked as “productivity”

❌ Waiting for perfect science before acting

8. Discussion

This evidence synthesis indicates that longevity is primarily influenced by modifiable lifestyle factors, with metabolic health and physical fitness forming the foundation. Pharmacologic and supplement-based interventions are emerging, but their impact is modest relative to foundational behaviors. Health professionals should prioritize integrated lifestyle interventions targeting metabolic optimization, musculoskeletal preservation, cardiovascular fitness, sleep, and stress resilience.

The “stack” framework underscores that if foundational layers—metabolic health, muscle mass, and cardiovascular fitness—are weak, higher-order interventions (supplements, specialized diets) have minimal impact.

9. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, direct evidence linking calorie restriction or metabolic interventions to increased human lifespan is lacking, as randomized controlled trials are necessarily limited to intermediate biomarkers and predictors of aging rather than mortality outcomes. Second, heterogeneity in baseline metabolic health, age, sex, and genetic background may substantially influence responses to calorie restriction, limiting generalizability. Third, most human trials are of relatively short duration compared with the human lifespan and cannot capture long-term adherence challenges, compensatory behaviors, or potential adverse effects such as loss of lean mass or reduced bone density. Finally, observational and mechanistic extrapolations from animal models may not fully translate to human physiology. These limitations underscore the need for personalized, metabolically informed approaches rather than universal longevity prescriptions.

10. Conclusion

Preservation of metabolic health, lean mass, cardiorespiratory fitness, sleep quality, and psychosocial engagement represent the most robust, evidence-based strategies to reduce premature mortality and extend healthspan. Future research should focus on interventions that combine multiple lifestyle factors in real-world aging populations.

References

Heilbronn LK, et al. “Effect of 6-Month Calorie Restriction on Biomarkers of Longevity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Oxidative Stress in Overweight Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA. 2006;295(21):1539–1548. PubMed

Most KM, et al. “A 2-Year Randomized Controlled Trial of Human Caloric Restriction: Feasibility and Effects on Predictors of Health Span and Longevity.” J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(9):1097–1104. PubMed

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. “Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis.” Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–423. PubMed

Kodama S, et al. “Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality.” JAMA. 2009;301:2024–2035. PubMed

Cappuccio FP, et al. “Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. PubMed

Epel ES, et al. “Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress.” PNAS. 2004;101(49):17312–17315. PubMed

Holt-Lunstad J, et al. “Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review.” PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. PubMed

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

Comments